What is Offshore Aquaculture? Defining the Phrase and Why it Matters

Offshore aquaculture has become an important, emerging sector of the aquaculture industry. While communities around the world are embracing it, their approaches can differ depending on their environment.

The Caribbean, for example, experiences hurricanes every year. This makes it essential to design farms that can withstand the waves and currents those storms create. Other farms, like some salmon producers in Norway, have selected sites with calmer conditions closer to shore. However, as those locations become more competitive, new farms are exploring the move into deeper waters.

Regardless of the driver pushing farmers to look further from shore and into high-energy environments, a big question remains: What does “offshore” mean exactly?

An Ambiguous Meaning

It’s perhaps not surprising that offshore aquaculture means different things to different people. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) uses the term “offshore” but never defines it. They aren’t alone. Several other legal documents, including the US’s National Offshore Aquaculture Act of 2005, do the same – mentioning the phrase but never offering a clear definition. Academic literature offers some definitions but always establishes the framework for the analysis therein and never as a standard meaning to be adopted by the industry at large.

To add further confusion, other stakeholders have started using the phrases “open ocean aquaculture” and “offshore aquaculture” interchangeably. Unfortunately, this has led to both becoming industry buzzwords more than anything else – with companies using them to present their fish or seafood from a pristine environment.

In this confusion, it’s become increasingly evident that the industry needs standard definitions that everyone agrees on. Doing so will allow for more pointed discussions and create a foundation for important conversations around policy decisions and operational best practices.

Defining Offshore, Open Ocean, and Exposed Aquaculture

The ICES Working Group for Open Ocean Aquaculture (WGOOA) has determined that the terms “offshore” and “open ocean” describe two related but ultimately distinct environments and has put forth definitions for each. Furthermore, the WGOOA has proposed utilizing the term, “exposed aquaculture,” to better describe the rough ocean conditions found at some farms.

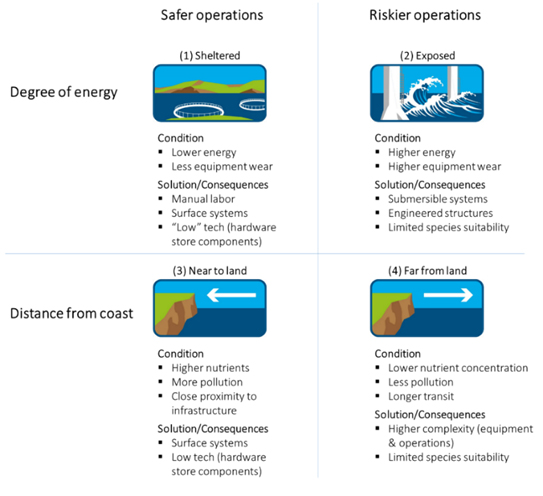

These definitions are centered around two challenges – geographical distance from shore and a farm’s exposure to high energy (large waves and strong currents). While related (farms further from shore typically experience rougher conditions), distance and energy levels are not always tied together.

Image courtesy of Bela Buck

In fact, there are many examples of farms that are close to shore but face large waves or, conversely, farms that are far from shore but operate in relatively calm waters. Below is a more detailed example from the WGOOA published in a special issue through Frontiers in Aquaculture.

For example, Farmer A is located at an exposed, nearshore site with up to 6 meters (m) significant wave heights, while Farmer B is located at a further distance from the coast but in shallower waters, sheltered and with lower wave heights. Farmer A invests in robust design and engineering to survive the strong forces of waves and currents. Farmer B has more of a focus on logistics, smart operational features, and the design and engineering needed to overcome issues related to the accessibility of the remote farm. Both farmers see their concepts as challenges, although these are fundamentally different development scenarios.

Nevertheless, the two farmers have one aspect in common; they are categorized as being part of “offshore aquaculture”.

With this in mind, here are WGOOA’s proposed definitions for “offshore aquaculture,” “exposed aquaculture,” and “open ocean aquaculture.”

Offshore aquaculture

WGOOA describes offshore aquaculture in terms of its geographical distance from shore. For a farm to be considered “offshore,” it needs to be 3 nautical miles from shore – roughly the distance something must be from shore to be obstructed from view.

Exposed aquaculture

A definition for “exposed” is more complicated and for this, a set of indices was created. Lojek et al. (2024) present six indices which reflect various aspects of ocean energy. One index, the Specific Energy Exposure index (SEE), is suggested as the go-to metric for discussing and evaluating farm sites. By adopting a single metric with a clear definition, all stakeholders will be able to communicate with each other speaking the same language.

A general understanding will develop as to what a farm looks like that has an SEE of 3, for example. This is difficult using simple wave metrics since there are several that are commonly used and none in themselves capture the full energy at the site. Describing a site as “having waves of 4m” is unclear as to whether that is the 50-year return wave, the largest wave the farm has observed, the average significant wave height, or simply a number the farm often sees on forecasts. It also provides no information on the wave period, let alone the current velocity. With this in mind, it would be possible for a farm to be both an offshore site and exposed.

Open ocean aquaculture

Finally, WGOOA proposed that the term “open ocean” remains a colloquial term for use when specificity is not required or for marketing applications.

Looking for ways to optimize your open ocean operations? Be sure to download the ebook: Succeeding in Aquaculture: How to Start and Run a Profitable Open Ocean Fish Farm.

Advancing the Conversation

Adopting defined and agreed-upon definitions into common industry usage will help establish the open ocean sector as a clearly defined interest group and provide a framework for classifying farms as offshore and/or exposed. With established exposed farms, the environmental and financial performance of these farms can be tracked and compared against other industry sectors to create a better understanding of the risks and benefits.

This adjustment is not unlike the one seen in land-based aquaculture with farms being separated into more-defined subcategories – whether that’s flow–through vs recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS), tropical vs temperate climates, or freshwater vs marine. By clearly defining each type, farms have received more precise gear, expertise, and guidance for improved results.

For more information, be sure to read the full special issue from Frontiers in Aquaculture.

Expertise for Your Situation

Whether you’re looking to start an open ocean or exposed aquaculture farm or optimize an existing one, we can help. Our teams of experts have the knowledge and experience to assist with all aspects of planning and optimization, from site and species selection to offering economic analysis to help guide you through the process.

Learn more about our aquaculture consulting services.

About the Author

Tyler Sclodnick is a senior scientist at Innovasea and leads the geographic information systems program. He also spearheads the company’s research program, which aims to improve the efficiency and sustainability of open ocean aquaculture systems. Prior to working in aquaculture, Tyler worked in ecology and conservation. He believes that aquaculture development can be compatible with environmental sustainability and conservation goals while also providing healthy protein and serving as an economic engine in coastal communities.

Tyler holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Biology from Queens University and a Master of Science degree in Marine Affairs and Policy from the University of Miami. He currently studying for an MBA at the University of Massachusetts.

Ready to get started?

Contact Innovasea today to find out how our aquaculture and fish tracking experts can help with your next project.